February 2025

Produced in partnership with Leavitt Partners

Produced in partnership with Leavitt Partners

Overview

Budget reconciliation is a legislative tool that can be used by the majority party in Congress to advance their agenda with only a simple majority in the Senate. With slim Republican majorities in both the House and Senate, reconciliation provides an opportunity to pass key components of President Trump’s agenda, such as defense and border security funding, tax cuts, and spending cuts, without Democrat votes.

Originally created to enable budgetary changes to help reduce the federal debt, budget reconciliation includes certain procedural elements (51-vote threshold in the Senate, no filibuster) that have made it a preferred method for passing legislation in certain policy areas on a party-line basis. However, reconciliation has some limitations, in that it can only be used for primarily-budget related provisions, such as changes to mandatory spending, revenue, and the debt ceiling. Programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) are examples of mandatory spending programs that can be changed through reconciliation. Reconciliation cannot be used to enact or rescind discretionary funding that is controlled through the annual appropriations process (e.g., funding for most Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration programs).

The budget reconciliation process started this month, when the House and Senate Budget Committees marked up separate budget resolutions, which provide instructions for congressional committees on proposals they need to put forward for a reconciliation bill. The Senate is planning on a two-track process where the first budget resolution, which was passed on February 21, 2025, directs relevant committees in the Senate to spend $340 billion on immigration enforcement, energy production, and the military. It was not focused on health care, evidenced by the direction to the Senate Committees with jurisdiction over health care (Finance Committee and the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee) to each include policies to reduce federal spending by $1 billion over the next ten years. The House’s budget resolution takes a significantly different approach in directing the Energy and Commerce Committee, which has jurisdiction over Medicaid and many other health programs (excluding most of Medicare), to propose $880 billion in savings over the next ten years. The House’s budget resolution instruction is expected to require significant changes to Medicaid in order to meet those instructions.

The rest of this issue focus provides an overview of Medicaid changes that could be proposed in a reconciliation bill and how those changes could impact states, Medicaid enrollees, and funders. The issue focus also provides information on how funders may choose to engage with Members of Congress on education and advocacy related to proposals being considered within the reconciliation process.

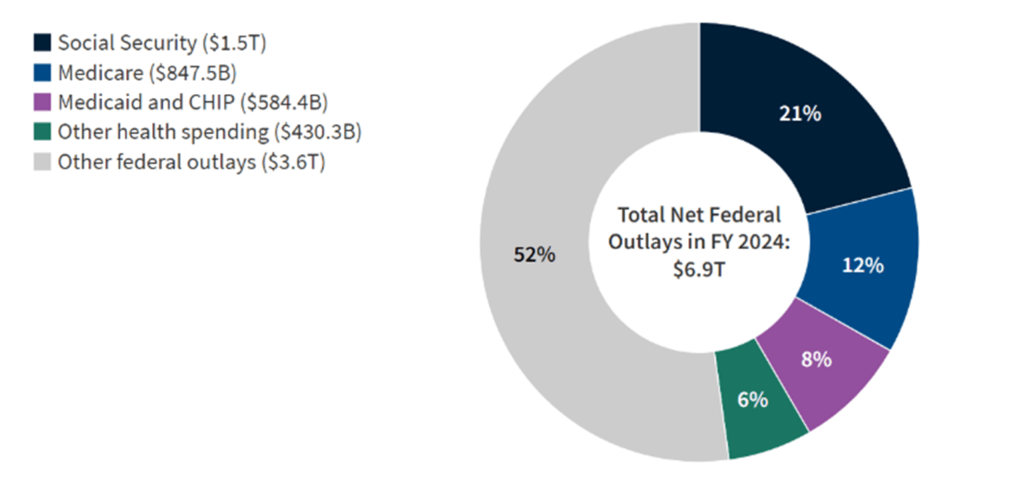

Federal Spending on Medicaid

Source: KFF

Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that provides health coverage to low-income individuals, including children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people with disabilities. In 2023, states received a total of $614 billion in federal funding for Medicaid and contributed $280 billion in state funds. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) expects that, under current law, federal spending for Medicaid will increase faster than overall inflation because of increases in health care prices, enrollment growth, and changes in utilization and technology (CBO 2024).

As of 2023, Medicaid covers more than 90 million low-income people, including about 39 percent of all children in the United States and 59 percent of all nonelderly individuals with income below the federal poverty level (Burns et al. 2025).

Because it represents a significant and growing amount of federal spending, Medicaid could be a source of proposals to reduce overall federal spending. In early February, the House committee provided information on a variety of Medicaid proposals with estimated savings that could be included in a reconciliation bill, such as reforms to limit the growth of the program and modify the federal match for certain populations. These changes could have very significant effects on people who rely on Medicaid for their health coverage and the providers who serve those patients.

POLICY OPTIONS TO REDUCE MEDICAID SPENDING

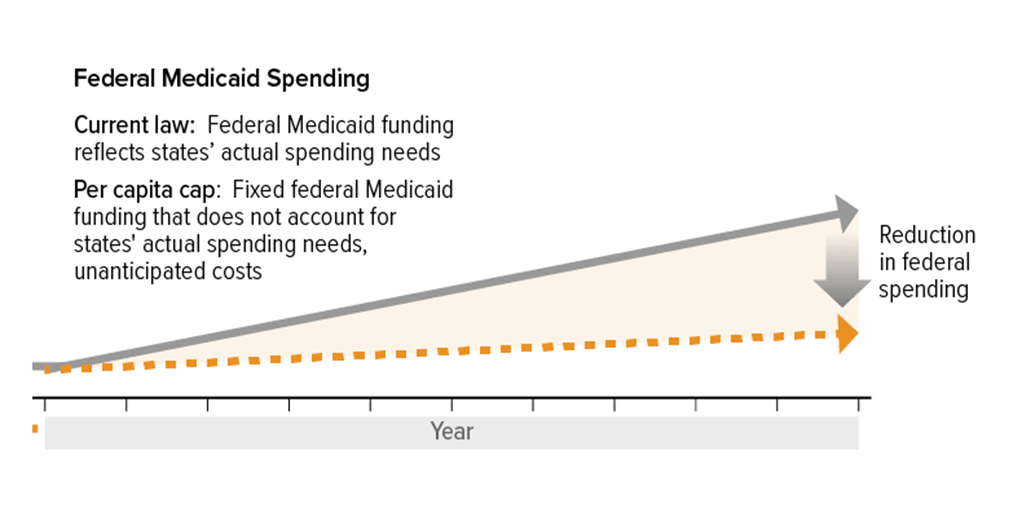

Per-Capita Caps

Under the current Medicaid financing structure, “there is no upper limit or cap on the amount of federal Medicaid matching funds a state may receive” (CBO 2024). Per-capita caps could establish fixed federal funding limits per enrollee in different eligibility groups, such as children, adults, elderly individuals, and people with disabilities, with the total federal payment to states equaling the sum of capped amounts multiplied by enrollment in each category. These per-capita caps could set a federal cap on per-enrollee spending amount using prior year expenditures, which could increase annually using a predetermined growth factor like the Consumer Price Index for Medical Care (CPI-M) (MACPAC 2017).

This reform would significantly impact state Medicaid programs in several ways:

- States would bear all financial risk for costs exceeding the federal cap. If health care costs rise faster than the growth rate used to adjust the cap, states would need to cover the difference or reduce expenditures (CRFB 2024).

- To manage within capped funding levels, states may need to reduce optional benefits, lower provider payments, or restrict eligibility for certain populations (CMS 2020).

Source: CBPP

The Congressional Budget Office estimates per-capita caps could reduce federal Medicaid spending by $900 billion over 10 years by slowing federal Medicaid spending growth (CRFB 2024). Per-capita caps could also shift additional costs to states, requiring states to increase Medicaid spending in future years or modify their programs to reduce costs. Several think tanks and health care stakeholders have released information on the potential impacts of per-capita caps, including the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and the American Hospital Association which both raise concerns that per-capita caps would force states to cut Medicaid benefits such as vision, dental, and home- and community-based services, cut eligibility groups such as individuals in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) expansion population (generally childless adults that make below 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level), and reduce payments to providers resulting in fewer providers accepting patients with Medicaid (Lukens et al. 2025; AHA 2025).

In 2017, Republicans included per-capita caps in a reconciliation bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act which passed the House but ultimately failed to pass the Senate. Some Republican House members have also expressed apprehension about the scope of Medicaid funding cuts in the current House Budget Committee’s budget resolution, as some stakeholders have been raising concerns about the impact of per-capita caps on state budgets as well as individuals and families who are enrolled in Medicaid.

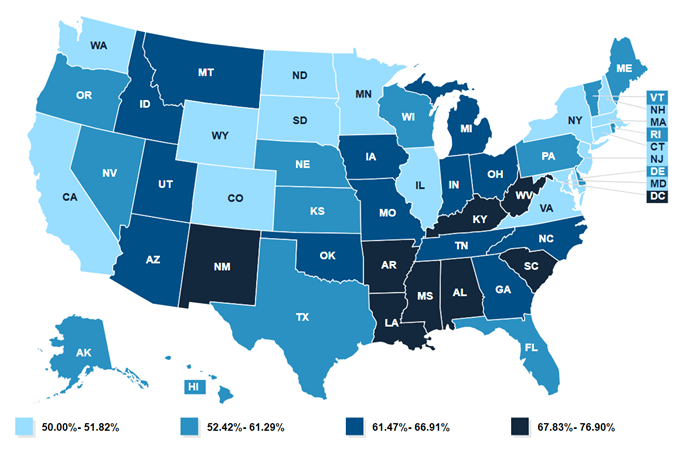

Lowering or Eliminating the FMAP Floor

The Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) determines how federal and state governments share Medicaid costs. Currently, FMAP rates have a statutory minimum of 50 percent (meaning the federal government covers 50 percent of the costs) and a maximum of 83 percent, with the exact percentage based on a formula that provides higher reimbursement to states with lower per capita incomes relative to the national average (CBO 2024). CBO estimates that reducing the FMAP floor from 50 percent to 45 percent could generate approximately $350 billion in savings over 10 years, while completely removing the floor could save up to $600 billion during the same period (CRFB 2024).

FMAP By State

Source: KFF

The impact of lowering or eliminating the FMAP floor would vary significantly by state. States that currently have an FMAP of 50 percent and would be impacted by lowering or removing the floor include California, New York, Colorado, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Washington (MACPAC 2024). However, states like Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas, and Mississippi have FMAPs between 57-77 percent and would not be impacted by lowering or removing the floor (MACPAC 2024). Proponents argue that lowering or eliminating the FMAP floor would create greater equity in federal Medicaid funding across states as wealthier states currently receive disproportionately more federal Medicaid funding per person in poverty than poorer states, despite the FMAP formula’s intent (MACPAC 2024).

States affected by a lower floor might need to increase state funding, reduce optional Medicaid benefits or eligibility or cut other budget priorities to maintain their programs (MACPAC 2020).

Repealing Recent Medicaid Rules

In 2023 and 2024, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued several rules addressing Medicaid access, eligibility, and enrollment. These rules were designed to expand access to Medicaid services, simplify enrollment processes, and improve program integrity (CMS 2024).

- The Medicaid Access Rule focused primarily on expanding access to Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) and requires that, in six years, states generally ensure a minimum of 80 percent of Medicaid payments for homemaker, home health aide, and personal care services be spent on compensation for direct care workers (CMS 2024). Repealing this rule is estimated to save $121 billion over 10 years.

- The Eligibility and Enrollment rules, issued in September 2023 and April 2024, streamlined eligibility verification and enrollment processes for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). These rules prohibited states from conducting eligibility checks more frequently than once every 12 months, eliminated in-person interview requirements, and extended modernized eligibility processes to non-MAGI populations (Federal Register 2024).

Repealing these rules could save an estimated $164 billion over 10 years. As provisions related to compensation for direct care workers have not yet fully in effect, repeal of these provisions of the rule would not have a significant impact on states and beneficiaries. Repeal of the eligibility and enrollment rules would allow states to implement more frequent eligibility checks and in-person interview and documentation requirements to show Medicaid eligibility. As states may implement policies to conduct Medicaid redeterminations more frequently, limit timeframes for individuals and families to provide Medicaid programs with information on eligibility, or increase eligibility verification requirements, some stakeholders are concerned this would create barriers to enrollment and increase the number of uninsured people.

Work Requirements

The House has also suggested it could include Medicaid work requirements (also referred to as community engagement requirements) in a reconciliation package. The House has previously passed the Limit, Save, Grow Act (H.R. 2811, 118th Congress) that would establish work requirements for able-bodied adults ages 19 through 55 to engage in community service, or participate in a work program (or a combination of these) for at least 80 hours per month to be eligible for Medicaid. H.R. 2811 exempted certain populations from the work requirements, including pregnant women, primary caregivers of dependents, individuals with disabilities or health-related barriers to employment, and full-time students. H.R. 2811 could provide a model for Medicaid work requirements in a reconciliation bill, and it is estimated that implementing this policy could reduce spending by $100 billion over 10 years. Additionally, CBO previously estimated that Medicaid work requirements in the Limit, Save, Grow Act would result in 1.5 million adults losing federal funding for their Medicaid coverage, of which an estimated 60 percent (or about 900,000 people) would remain in their states’ Medicaid program under state-only funding and 40 percent (or about 600,000 people) would become uninsured (COB 2023). Between June 2018 and March 2019, Arkansas implemented Medicaid work and reporting requirements, during which time “more than 18,000 people lost coverage, or about 25 percent of the population subject to the requirement, primarily due to failure to regularly report work status or document eligibility for an exemption (Hinton 2025).”

Other Medicaid Financing Changes

In addition to the changes already described, there are also a number of other Medicaid financing changes that Congress could enact. The common theme among these is that they are various ways to limit federal Medicaid spending or limit the ways that states can generate their share of the required state match. Each of the examples below could be dialed up or down to meet the Congress’ savings target. This is a small selection of these sorts of policies, not a comprehensive list:

- Placing a per capita cap on the ACA Medicaid expansion population or making changes to the enhanced 90 percent FMAP that states receive for the ACA Medicaid expansion population (individuals whose income is under 138 percent FPL and do not otherwise qualify because of being a parent, elderly, disabled, or a minor).

- Changing the FMAP for administrative expenses.

- Limiting the use of Medicaid provider taxes, which are a mechanism states have used since the 1990s to increase the amount of state funding available for Medicaid to generate additional federal matching payments.

- Limiting the use of “state directed payments” which are used to “steer additional payments to providers to help the state achieve certain Medicaid goals.” According to the Government Accountability Office, “state directed payments should have been exceptions to the regular payment process, but they now comprise a significant and growing proportion of managed care spending (GAO 2023).”

- Limiting eligibility based on citizenship status.

Implications for Funders

Since each state operates their own Medicaid program, the impacts of these policies, if passed, will vary by state and could take several years to implement. Overall, the policies would reduce federal spending on Medicaid, putting pressure on states to make up the difference, which can be challenging for states that have to balance their budgets, and could require difficult tradeoffs for states such as cutting other state funding or limiting Medicaid benefits or eligibility.

Specifically, in response to changes that reduce or slow the growth of federal Medicaid spending, states could limit the optional services covered by Medicaid, such as dental services, physical and occupational therapy, case management, and services to address health-related social needs like housing and food (more information on mandatory and optional services is available on CMS’ website). States could also adjust provider payment rates or make changes to populations covered by their state Medicaid program, including limiting eligibility for the ACA expansion population or other individuals based on citizenship status. Limiting eligibility or covered services could result in more people being uninsured or not having coverage for many services and increase the need for private funding for populations, health care services, and health-related services that are not required to be covered by Medicaid.

Funders have a number of opportunities to influence the current debate through education and advocacy efforts. These may include:

- Paying attention to compelling data and analyses of the potential impacts of specific policy proposals. In particular, think tanks, states, providers, beneficiary advocates, and other stakeholders will be seeking to interpret the effect of policy proposals and may offer analyses of the coverage and economic impacts, or other ways of describing the proposed changes.

- Educating and engaging with members of Congress on the impacts of these policies on their constituents, including for specific populations which may include individuals on Medicaid receiving treatment for substance use disorders, seniors, pregnant women, children and other priority populations for funders.

- Educating and engaging with members of Congress on impacts to providers, such as community health centers, primary care providers, and hospitals in the member’s state or district.

- Coordinating with other stakeholders, such as health care providers, patient groups, and Medicaid managed care organizations, on outreach efforts.

- Engaging traditional and social media to educate the public about the policy changes and seek to influence key Senators and House members.

What’s Next

House Republican leaders have indicated that they will take the House Budget Committee passed budget resolution to the House floor as soon as February 24. The House Rules Committee will set the debate time and whether any amendments will be in order.

While the House budget resolution has directed significant reductions in federal spending, incredibly slim margins in the House Republican majority mean they cannot lose a single vote for a budget resolution or a reconciliation bill, which creates particularly challenging dynamics as each member considers the needs of their district and state. In contrast, the Senate budget resolution passed by the Senate does not envision a similar scale of cuts. Ultimately, if the House and Senate pass differing reconciliation bills, they will need to conference the bill or conduct informal negotiations to come to agreement, and both chambers will need to vote to pass a conference report or identical budget resolutions in order to officially begin a budget reconciliation process.

How You Can Help

Families USA, along with Community Catalyst, the National Health Law Program, Service Employees International Union, and hundreds of national and state partners will speak directly to Congress and tell them to keep their “Hands Off Medicaid.” Click here to learn how you can join this effort.

Additional Information and Resources

KFF offers a web page providing a comprehensive look at Medicaid, along with reports, news, and updates about the proposed cuts.

The Commonwealth Fund has created a useful interactive map to help readers understand how Medicaid affects their states.

The National Health Law Program is offering resources and analysis for staying informed and mobilizing advocates to protect Medicaid’s promise of accessible, comprehensive care.

The California Health Care Foundation compiled resources on Defending Medi-Cal in 2025 to help advocates, policymakers, health care leaders understand Medi-Cal and stay abreast of federal policy changes:

American Hospital Association (AHA). Fact Sheet: Per Capita Caps in the Medicaid Program. Washington, DC: February 2025.

Burns, Alice, Elizabeth Hinton, Robin Rudowitz, and Maiss Mohamed. “10 Things to Know About Medicaid.” KFF. February 18, 2025.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Ensuring Access to Medicaid Services Final Rule (CMS-2442-F). Washington, DC: April 22, 2024.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Healthy Adult Opportunity Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: January 30, 2020.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicaid & CHIP Eligibility and Enrollment Final Rule. Washington, DC: May 29, 2024.

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB). “Medicaid Savings Options.” December 12, 2024.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Establish Caps on Federal Spending for Medicaid. Washington, DC: December 12, 2024.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Letter to Representative Jodey Arrington from Phillip L. Swagel. April 25, 2023.

Federal Register. Medicaid Program; Streamlining the Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, and Basic Health Program Application, Eligibility Determination, Enrollment, and Renewal Processes. Washington, DC: April 2, 2024.

Hinton, Elizabeth, and Rubin Rudowitz. “5 Key Facts About Medicaid Work Requirements.” KFF. February 18, 2025.

Lukens, Gideon, and Elizabeth Zhang. “Medicaid Per Capita Cap Would Harm Millions of People by Forcing Deep Cuts and Shifting Costs to States.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. January 7, 2025.

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Design Issues in Medicaid Per Capital Caps: An Update. Washington, DC: July 2017.

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Exhibit 6: Federal Medical Assistance Percentages and Enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentages by State, FYs 2022–2025. Washington, DC: December 2024.

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). “Matching rates.” December 23, 2020.

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Medicaid Managed Care: Rapid Spending Growth in State Directed Payments Needs Enhanced Oversight and Transparency. Washington, DC: December 14, 2023.

Topics: