Havaca Ganguly, MPA, Executive Director, The Middendorf Foundation

Jennifer Wright, MPH, Senior Program Officer, The California Wellness Foundation

Rabera, MA, Program Lead for Health Justice Organizing & Advocacy, Universal Health Care Foundation of Connecticut

Erica Browne, DrPH, Senior Program Officer, The Kresge Foundation

Trends in leadership are changing—just take the Terrance Keenan Institute (TKI) as an example. When the program started in 2010, it focused on general leadership tactics with topics that ranged from leveraging resources and building partnerships to board dynamics. Since then, the Institute’s curriculum has moved towards a recognition that leaders possess individual strengths that can be embraced to make our organizations and the broader field of health philanthropy more effective.

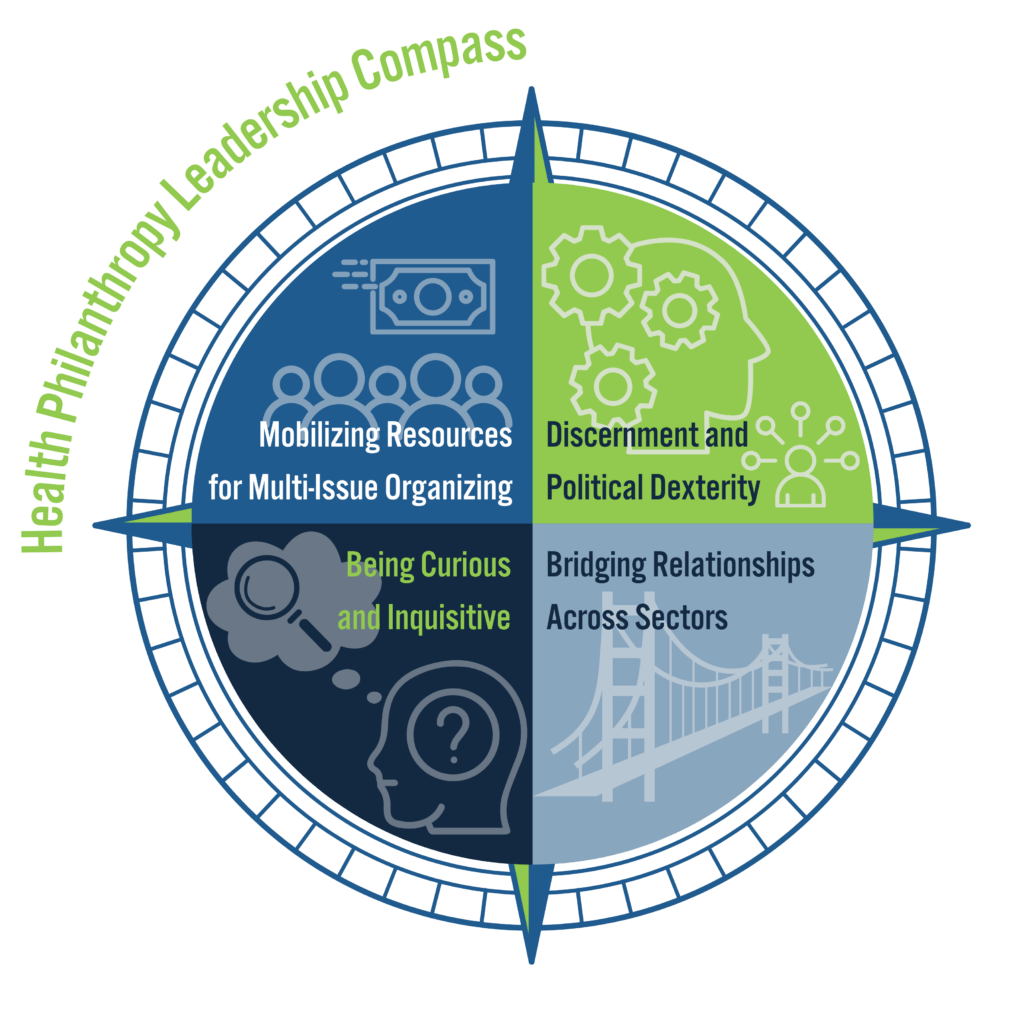

As we emerge from the experience of a global pandemic that has exacerbated health inequities, accelerated technological innovations, and sharpened political threats, the complexity we currently face requires us to lead with shared values that draw from individual strengths rather than tactics. As TKI fellows who lead from different positions within a variety of philanthropic institutions across the United States, we believe that discernment, curiosity, relationship bridging, and multi-issue problem-solving remain indispensable skills to guide emerging leaders in health philanthropy. Instead of relying on a singular North Star, these leadership attributes can serve as a compass to help us navigate the complexity of our work and identify an array of stars whose light we can amplify along the way.

Demonstrating Discernment and Political Dexterity

Power greatly influences the dynamics of relationships and decision-making in philanthropic organizations charged with resourcing other organizations. Leaders working to shift power have the ability to nurture relationships based on trust, support, and solidarity to advocate for health philanthropy to follow the lead of communities and prioritize organizations led by people with lived experiences. By trusting organizations, we can shift our organizational resources into efforts guided by grant funded partners and their autonomy (Nangle and Kearney 2023). By using discernment, we can self-examine and identify which practices impede the success of our grant-funded partners. Trust, accompanied by contextual awareness and flexibility, can facilitate the provision of unrestricted multiyear grants that enable our partners to address complex political dynamics without the burden to constantly chase funding.

Often, the lesson has been for philanthropy to be open and flexible in advocacy and organizing spaces. Yet the power one wields in these spaces should be directed to strengthen the movement by bridging resource gaps (Keidan 2023). Philanthropic leaders can take a chance on small grassroots organizations, collectives, and volunteer-run organizations doing incredible work (Barsoum 2023). We can eliminate the barriers that prevent resources from reaching these organizations and remember the purpose of their work in the broader political context. Otherwise, the hurdles we create will continue to marginalize the very organizations we committed to support in our post-2020 revamped mission and vision statements.

Being Curious and Inquisitive

There is a false narrative that suggests great leaders must be the experts in the room and have all of the answers. In reality, leaders in health philanthropy need to be inquisitive and foster a sense of curiosity within their institutions. Leaders must be willing to interrogate the way we do our work and ask ourselves if we are funding to maintain the status quo or if we are actually willing to make bold changes to advance systems change, racial justice, and the like. In recent years, several philanthropic institutions have been on a learning and unlearning journey to apply more equitable evaluation practices, and there is more work to be done to shift the field as a whole.

An important first step is to actively listen to those who are most impacted by the complex issues we seek to address in our work. For example, The California Wellness Foundation worked with Black woman-led evaluation teams who brought forth both academic and lived experience expertise to inform the learning approach for the Women of Color Health Initiatives. The evaluation questions and data collection were also codesigned with grant-funded community partners to ensure that the right questions were being asked and that learnings were relevant to those on the ground providing services and doing the work. To see transformational change, leaders must be ready and willing to shift away from transactional grant monitoring to a posture that truly values community expertise and the inclusion of more voices and perspectives in decision-making.

Bridging Relationships Across Sectors

Another indispensable strength necessary to lead in health philanthropy is having a visionary approach to help weave together community aims and assets, forge stronger relationships with private and public sector funders, and collaboratively engage local organizations and business. Philanthropic leaders are uniquely positioned to build public sector relationships that actualize social change by focusing on the public policy ecosystem (Jagpal and Laskowski 2013). As an example, for Universal Health Care Foundation of Connecticut, achieving health and justice for all requires an ecosystem of diverse organizations that can collectively influence the structures where ideas, policies, and power are contested in partnership with other organizations and stakeholders across the state.

Emerging leaders can build relationships with private sector businesses, nonprofit organizations, and government agencies to establish shared goals that strengthen the ecosystem of social change. For example, the Bridging Strategies and Partnerships Program helps build deep and trusting relationships between health departments and community power building organizations to advance policy and systems change on the social determinants of health. Similar efforts can support equitable investment and systems change among hospitals and health systems (Hacke and Deane 2017). Bridging across sector silos involves investing considerable time to build relationships to cultivate diverse funding streams, long-term investments, and equitable capital pipelines.

Mobilizing Resources for Multi-Issue Organizing

The ability to mobilize resources to support multi-issue organizing and community-centered solutions is integral to our work as leaders in health philanthropy. Because the communities we serve simultaneously experience multiple, interconnected and complex issues, we must expand our narrow view of strategy and single-issue silos to focus on systems change in a manner that builds relationships, mutual accountability, and power across constituencies (Jagpal and Laskowski 2013). At the Kresge Foundation, the multi-issue organizing of its community safety and Climate Change, Health and Equity place-based partners has required a more creative and responsive mobilization of strategic communications, technical assistance, leadership development, convening, and funding resources to support their work. For leaders in health philanthropy, this expansive way of conceptualizing and doing our work requires us to embrace complexity (Stamp and Choi 2021). The Middendorf Foundation, for example, funds across the Arts & Culture, Healthcare, Environment, Social Services and Education nonprofit sectors to help strengthen a nonprofit ecosystem that advances social justice across various issues. Grantmakers in Health, and other organizations in the field, can organize meetings, peer learning, and leadership development activities that foster greater collaboration and resource mobilization for multi-issue organizing among health funders.

A Call to Action

The opportunities to cultivate these indispensable leadership attributes within health philanthropy are multitudinous. Individuals can mentor and sponsor new leaders by spotlighting their strengths, affirming their demonstrated leadership, bridging beneficial relationships, and protecting their eminence (Chow 2021). Organizations can nominate emerging leaders to the 2024 Terrence Keenan Institute and support their successful participation. Emerging leaders can seek personal and professional development opportunities that inspire curiosity, cultivate emotional intelligence, and foster mutually beneficial relationships among diverse partners. Grantmakers in Health and other philanthropy-serving organizations can emphasize political acumen and dexterity, active learning and curiosity, relationship bridging, and multi-issue resource mobilization across all programs. As a field, health philanthropy must rigorously examine and eliminate the self-imposed barriers that stifle our ability to cultivate more diverse and inclusive leadership. Where will you start?

Resources and References

Barsoum, Gigi. “A New Framework for Understanding Power Building.” Stanford Social Innovation Review. July 17, 2023.

Chow, Rosalind. “Don’t Just Mentor Women and People of Color. Sponsor Them.” Harvard Business Review. June 30, 2021.

Hacke, Robin, and Deane, Katie Grace. Improving Community Health by Strengthening Community Investment: Roles for Hospitals and Health Systems. Washington, DC: Center for Community Investment, March 2017.

Jagpal, Niki, and Laskowski, Kevin. Smashing Silos in Philanthropy: Multi-Issue Advocacy and Organizing for Real Results. National Committee For Responsive Philanthropy. Washington, DC: National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, November 2013.

Keidan, Charles. “Should philanthropy be more political?” Alliance. December 5, 2023.

Nangle, Claire Gibson, and Kearney, Devon. “To shift power, fund entire ecosystems.” Alliance. January 10, 2023.

Stamp, Trent., and Choi, Cathy. “Philanthropy’s Problem With Single-Issue Solutions.” Stanford Social Innovation Review. April 26, 2021.