Lindsay Rosenthal, Director, Ending Girls’ Incarceration Initiative at Vera Institute of Justice

Julia Arroyo, Executive Director, Young Women’s Freedom Center

The United States leads the world in incarceration rates of women and girls—we account for only 4 percent of the world’s population of women and girls but 30 percent of women held in prison and jails (Kajstura 2018). Many girls are incarcerated not because they pose a threat to the public but because of concerns for their own safety in the community—such as abusive home environments (Saar et al 2020). California incarcerates more girls than any state other than Texas and can lead the way on ending girls’ incarceration nationwide.

The Vera Institute of Justice (Vera) and Young Women’s Freedom Center (YWFC) are working together to end girls’ incarceration in California and have shown it is possible through scaling successful efforts to get to zero in Santa Clara County statewide. In 2023, the California Health and Human Services’ Office of Youth and Community Restoration committed to end girls’ incarceration by launching the End Girls’ Incarceration in California Action Network, which brings together counties to implement community-led solutions that promote healing and well-being.

Recently, we released a report, Freedom and Justice: Ending the Incarceration of Girls and Gender-Expansive Youth in California,which provides data on how girls are impacted by California’s youth legal system. To capture the experiences of those impacted by incarceration, YWFC conducted 50 interviews with girls and gender expansive youth (including nonbinary, transgender, and gender nonconforming young people). Relying on the voices of the interviewees and learning from our efforts working together, the report provides a roadmap for getting to zero statewide.

Here are highlights:

- California is very close to bringing a permanent end to girls’ incarceration. Between 2012 and 2022, girls’ arrests in California have fallen by 81 percent and girls’ detention admissions by 72 percent. In 2022, there were just under 1,400 detentions of girls statewide, meaning that in any individual county, numbers are small. In fact, 30 counties in the state had a 12-month average daily population of fewer than five girls in custody, and 20 counties had at least one day during 2022 when there were no girls in any facility. Almost half (43 percent) of detentions were on low-level charges system stakeholders generally agree pose no serious threat to community safety and should be diverted.

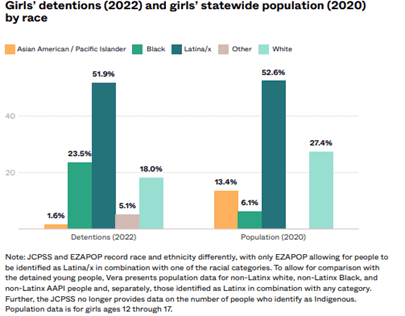

- Despite progress, ending girls’ incarceration remains urgent and necessary to address race and gender equity. Girls of color are more likely to be detained than their white peers and disparities are particularly stark for Black girls. Black girls make up 24 percent of all girls’ detention admissions despite accounting for only 6 percent of all girls in California. LGBTQ+ youth are also disproportionately impacted. As many as 51 percent of young people incarcerated in girls’ units in California identify as lesbian, bisexual, questioning, gender nonconforming, or transgender.

- Girls and gender expansive youth say that investing in healing and support, rather than punishment, is the path to ending incarceration—and research backs their perspective. Research has clearly shown that incarceration neither addresses safety or mental health needs, nor redirects young people away from legal system involvement as effectively as community-based interventions that promote well-being (Ernest 2019; Strang et al 2013).

When asked about solutions, youth interviewed for our report recommended investments in community-based healing, therapy, and mentorship resources; housing and material economic support; and opportunities to engage in advocacy and give back to their communities. Here’s some of what they had to say—please note that their names have been changed to protect their identities:

“I’m still healing from a lot of things that I [went] through…. I wish I had learned these tools to take care of myself and heal so I could move in the world better instead of moving with hurt and hurting other people.” — Lillian

“Honestly, I want to see more culture. I think that’s healing. I honestly believe bringing back your roots [is the solution]. Who wants to walk around knowing that they don’t know where they come from?” — Teuila

“I need to be in spaces that are healthy and that are healing, as well as educational, so that I can be sure to be able to help my community and look to my elders for their guidance…” — Anna

Gender-responsive program models, like YWFC, provide this type of support. They use a holistic approach, centered around overall well-being and focused on lifting up resilience and building capacity to access resources. This approach addresses the structural factors that bring girls into the legal system and that are shaped by gender, race and power imbalances—such as lack of housing, lack of safety, or mental health challenges (Javdani and Allen 2014[JB2] ). Evidence shows that these community-based models produce better outcomes (Granski et al 2019; Javdani 2013). They are also far cheaper than incarceration, which can be more than $500,000 per youth per year (Johnson 2020).

October is Youth Justice Action Month: Take Action to Get to Zero

Funders can support ending girls’ incarceration by investing in community-led efforts to promote healing and by amplifying the voices of young people and the solutions that they champion. To join us in recognizing Youth Justice Action Month, please share this Views from the Field article. To learn more about how girls are impacted by the California youth legal system and view additional recommendations, please visit Freedom and Justice: Ending the Incarceration of Girls and Gender-Expansive Youth in California.

Ernest, Kyle. Is Restorative Justice Effective in the U.S.?Arizona State University. Tempe, Arizona: August 2019

Granski, Megan, Shabnam Javdani, Valerie Anderson, and Roxane Caires. “A meta-analysis of program characteristics for youth with disruptive behavior problems: The moderating role of program format and youth gender.” American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(1-2), 201-222, August 2019.

Javdani, Shabnam. (2013). Gender matters: Using an ecological lens to understand female crime and disruptive behavior. In B. L. Russell (Eds.), Perceptions of Female Offenders: How Stereotypes and Social Norms Affect Criminal Justice Responses (9-24). New York: Springer.

Javdani, Shabnam, and Nicole E. Allen, “An Ecological Model for Intervention for Juvenile Justice-Involved Girls: Development and Preliminary Prospective Evaluation,” Feminist Criminology 11, no. 2, 135-162, December 2014.

Johnson, Sydney. “Some California counties are paying more than $500,000 per youth to lock up young people.” EdSource. November 20, 2020.

Kajstura, Aleks. “States of Women’s Incarceration: The Global Context.” Prison Policy Initiative, June 2018.

Saar, Mailka Saada, Rebecca Epstein, Lindsay Rosenthal, Yasmin Vafa. The Sexual Abuse to Prison Pipeline: The Girls’ Story. Human Rights Project for Girls, The Center on Poverty and Inequality, and The Ms. Foundation for Women. Washington, DC: June 2020.

Strang, Heather, Lawrence William Sherman, Evan Mayo-Wilson, Daniel Woods, and Barak Ariel. Restorative Justice Conferencing (RJC) Using Face-To-Face Meetings of Offenders and Victims. Campbell Systematic Reviews. Oslo, Norway: November 1, 2013.