The critical connection between water and health can be found in almost every aspect of our lives. For most, this link is the water from the taps in our homes, where we expect to find clean, safe water to drink, shower, brew coffee, and brush our teeth. The recent tragedy in Flint, Michigan has reminded us that we should not take access to safe drinking water for granted. Children are particularly vulnerable. For example, a dose of lead that would have little effect on an adult can have a significant and irreversible effect on a child.

Ensuring access to sufficient, safe drinking water has been an essential function of water utilities, public health, and health care professionals around the world for more than a century. The public health community is often on the front lines, responding to elevated blood lead levels—and can speak to the need for prevention. One of the main reasons for lead contamination in our drinking water is the millions of water lines still made of lead. Funders who are leading the way in health can help address this challenge.

Sources of Lead in Drinking Water

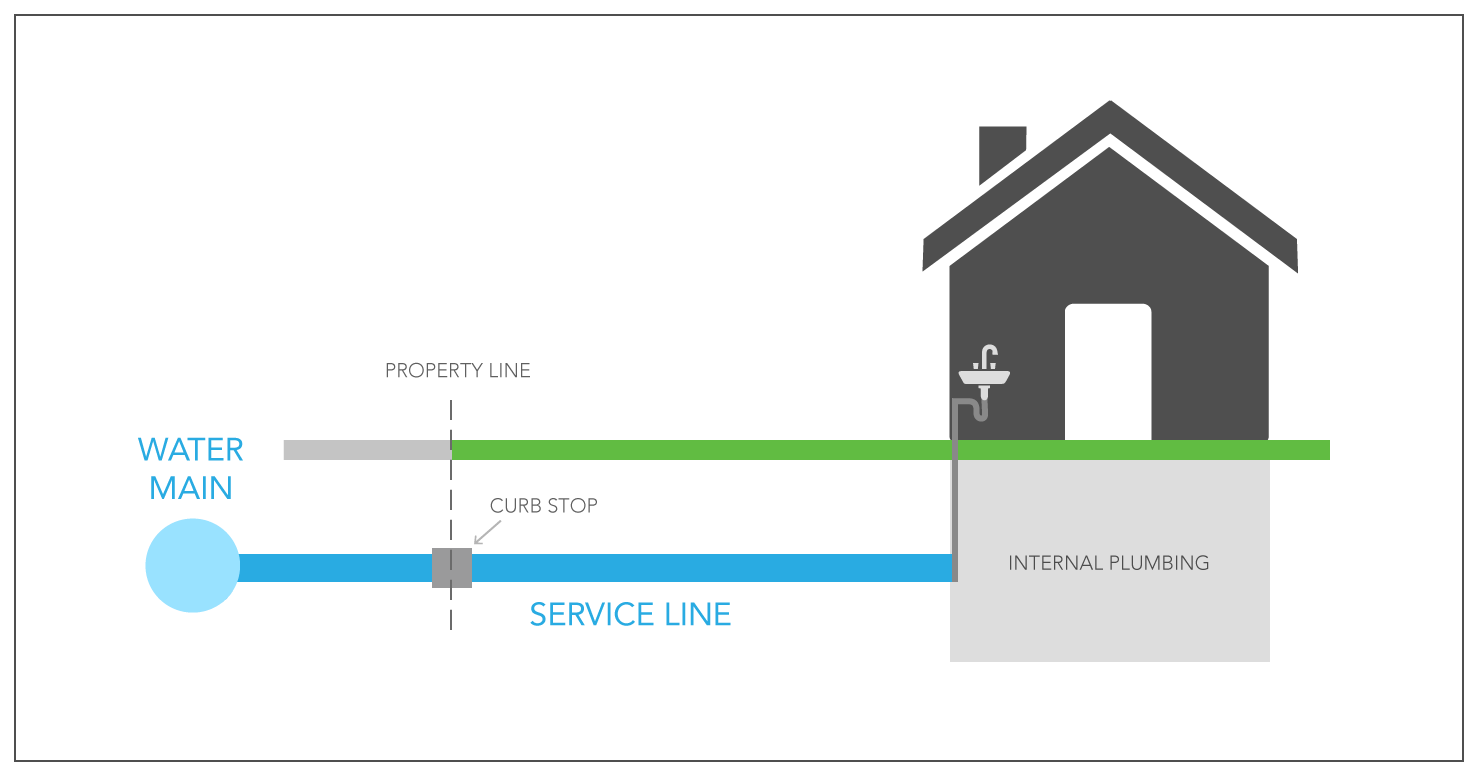

Lead can enter drinking water after it leaves a treatment plant when lead pipes or plumbing fixtures corrode, which is more likely to occur when water has high acidity or low mineral content. There are three primary sources of lead that can enter drinking water (Diagram 1):

- Lead pipes that connect the water main under the street to a building, commonly referred to as lead service lines or LSLs

- Leaded solder used to connect copper pipe and fittings

- Brass used in faucets and other plumbing components

Although Congress banned lead pipes, banned leaded solder, and limited the amount of lead in brass in 1986 and again in 2014, current estimates suggest that six to 10 million lead service lines remain. Low wealth and underserved communities tend to be disproportionately exposed to lead. People of color are twice as likely to have elevated blood lead levels, and children from underserved communities are three times more likely to have elevated blood lead levels. Coordinated action is needed to protect the more than half million children with elevated blood lead levels and others at risk for lead exposure.

What Can We Do?

While consensus to replace lead service lines began before the crisis in Flint, the visceral impact caused by the shocking and preventable harm to children prompted the formation of the Lead Service Line Replacement Collaborative, a diverse group of 24 national public health, water utility, environmental, labor, consumer, and housing organizations. The collaborative is funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Pisces Foundation, and by the in-kind contributions of its members. Collaborative members have different perspectives on many issues, but are united in their efforts to accelerate the full replacement of lead service lines through coordinated efforts at the local level.

As a first step, the collaborative compiled information from communities with replacement initiatives underway into a publicly-available toolkit to make it easier for other communities to get started. Launched in January 2017, the collaborative’s website contains questions to ask when planning a lead service line replacement initiative, technical information for implementing replacement, and policies to consider that could accelerate full replacement. Additional website information includes:

- Ways to inventory where lead service lines remain

- Factors to consider when selecting among replacement techniques

- Health and safety considerations

- Strategies for communicating with consumers

The collaborative welcomes feedback about what additional information would be helpful and will soon be reaching out to local communities across the country to prompt conversations and action. Foundations and corporate giving programs, with their deep roots in many communities, can play an important role in encouraging and sustaining these conversations.

What Will It Take?

Replacing lead service lines costs money. With six to 10 million lead service lines to replace, cost estimates range from $16 billion to $80 billion nationwide, and several thousand dollars per residence. Who pays for what varies in different states and locales. Through basic water bills, customers typically fund general costs, such as developing an inventory of lead service lines, designing the replacement initiative, and communicating to consumers. Ratepayers also typically pay to replace the portion of the lead service lines in the public right-of-way. Paying for the replacement of the portion of the lead service lines on private property can be more complicated.

If individual ratepayers with lead service lines are required to fund the replacement of the line on their property, people with the financial wherewithal are more likely to make the investment. Incentives to pay for replacement also may differ for rental versus owner-occupied residences. As a result, low wealth residents may be disproportionately at risk.

In some states, utilities are prevented by law from paying for work on private property. However, new approaches for lead service line replacement funding, including both government loan and grant programs, are being explored in Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Virginia, and elsewhere. The public utility commission in Pennsylvania has granted a waiver to one utility, allowing them to pay for lead service line replacement on both public and private property. These experiments are encouraging because the best funding mechanism—one that will benefit all consumers in an equitable manner regardless of income, race, or ethnicity—will likely depend on a combination of factors unique to each community.

We believe that through advocacy, collaboration among a broad spectrum of groups, new thinking, and technologies, we can remove lead from contact with drinking water. Water utilities are stepping up efforts to remove lead service lines, but they need the involvement of community leaders, public health, and health care professionals who have expertise in lead poisoning prevention, community engagement, and risk communication. The philanthropic community can have a role in fostering innovative approaches and supporting collaboration. If health and water funders work together, we can help communities make improvements to drinking water safety that will result in significant public health gains for millions of Americans.

For a public health overview, view the webinar “Protecting Children from Lead Exposures through Water: Introducing the LSLR Collaborative”. For examples of newly launched state funding programs, view the webinar: “Lead Service Line Replacement – Ideas for States”.