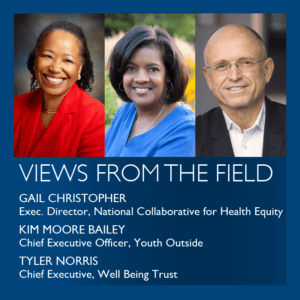

Gail Christopher, Executive Director, National Collaborative for Health Equity

Gail Christopher, Executive Director, National Collaborative for Health Equity

Kim Moore Bailey, Chief Executive Officer, Youth Outside

Tyler Norris, Chief Executive, Well Being Trust

In recent weeks, we have seen people around the world turn to nature for reprieve and respite from the stress and uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Mounting research, combined with our personal and professional experience, suggest that improving equity in access to greenspace may help combat health inequities. Access to safe, nearby nature must be prioritized as critical public health infrastructure and not just an amenity for a few.

With each passing day of this crisis, it becomes clear that too many children and families lack equitable access to the benefits of nature at a time when they need it most. Just as systemic racism impacted the design and distribution of parks and greenspaces, African American and Latinx people in the U.S. are disproportionately dying from COVID-19 in yet another tangible reflection of the true cost of inequitable systems. As we think about how to help communities emerge from this crisis, will we repeat the mistakes of the past, or will we think holistically about what truly supports health and well-being? Let’s not make false binary choices between things like food, shelter, and transportation or access to education, jobs, health care, and nearby nature. People need all of these things to thrive.

There is substantive science behind what many intuitively understand: spending time in nature makes us feel better. Studies show that nature’s benefits are relatively greater for those who are negatively impacted by economic disadvantage, systemic racism, trauma, opportunity gaps, and other challenges. Three main factors emerge from the research on nature’s health benefits that are particularly relevant right now, especially in communities most impacted by systems of inequity: 1) a sense of calm, restoration, and a measurable reduction in stress, 2) enhanced mood, reduced anxiety and depression, and 3) improved resilience and ability to cope with adversity.

The most robust area of research is around stress, with increasing evidence that regular connection to nature helps people feel calmer and less stressed. Studies show that when people are overloaded by adverse experiences, our stress response systems run in high gear pumping out cortisol, which—without recovery—negatively impacts sleep, metabolism, and other physical systems. In short, a stress response system in high gear decreases our ability to focus and increases the likelihood of illness. In an experimental study, views of green landscapes from classroom windows helped high school students recover more quickly from stressful events (Li and Sullivan 2016). In Germany, 11-year old students were either taught indoors or spent a day a week over the course of a year learning outdoors in forest school programs. The kids who participated in forest school showed a normal, healthy decline of cortisol levels over the course of the morning. This decline in the stress hormone was not found in the indoor control group suggesting a more chronic level of stress in children taught indoor (Dettweiler et al. 2017).

A 2020 review of peer-reviewed studies, found that as little as 10-20 minutes in nature daily may serve as a preventative measure for stress and mental health strain for people between the ages of 18-22 years old (Meredith et al. 2020). Physiological health markers of stress associated with time in nature included decreased heart rate and blood pressure. Psychological indicators of reduced stress associated with time in nature included less depression, anxiety, and fatigue, and increased vigor, positive affect, and feelings of calm. A 2018 systematic literature review examined the impact of greenspace on a wide range of health outcomes. The combined population of the studies exceeded 290 million people from 20 different countries across all age ranges. Meta-analysis of the data showed that greenspace exposure was linked to statistically significant reductions in diastolic blood pressure, salivary cortisol (a physiological marker of stress), heart rate, and incidence of diabetes. Findings also indicated that exposure to greenspace reduces the risk of preterm birth, premature death, and high blood pressure (Twohig-Bennett and Jones 2018). Some studies found that the association between greenspace exposure and positive health outcomes was stronger for people with low socioeconomic status and living in communities most negatively impacted by systemic racism, trauma, opportunity gaps, and other challenges. These findings are consistent with other research indicating a possible protective association between green surroundings and the risk of depression and other mental health concerns, indicating that nature can help mitigate harmful effects of unhealthy conditions.

So, what can health funders do? Investment is needed in national backbone organizations that provide research, build capacity, and work at the systems level to increase equitable access to the benefits of nature. The work of nonprofits like Youth Outside, Outdoors Alliance for Kids, the National Recreation and Parks Association, the Children & Nature Network, the North American Association of Environmental Education, and others is critical right now in providing information and resources for connecting to nature safely during the pandemic. Their work will be even more critical as leaders and communities think about nature connection as they plan for a new normal post COVID-19.

Additionally, support is needed for the development of national, state, and local policy initiatives that encourage equitable access to the outdoors. For example, the Youth Outdoors Policy Partnership offers a policy playbook that highlights innovative initiatives from across the country. As we move forward in the coming months, we will need policies and programs that support access to nature-based learning, play, and recreation in neighborhoods, schools, childcare centers, and libraries. Nature experiences should be a regular part of both in-school and out-of-school activities for children, young people, and families. Policies that support access to nature for seniors and people with disabilities can help ensure that people across the age span benefit from the healing power of nature.

At the local level, we need to invest in and create more parks, greenspaces, urban agriculture, and outdoor learning, adventure and camping programs, especially in neighborhoods where they don’t exist. Programs that provide safe and culturally relevant outdoor programming should be well funded. Meaningful community engagement in designing and evaluating such programs should be a priority.

As a global community, we are realizing, and remembering, how much we need nature, perhaps now more than ever. We urge funders to help carry forward the lessons we are learning during the COVID-19 crisis about the important role that nature plays in supporting health and well-being, especially for those most impacted by systems of inequity. Now is the time to invest more in ensuring that equitable access to nature exists in every community, to support health and well-being, and to build the resiliency of people and the planet.

References

Li, D. and W.C. Sullivan. “Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue.” Landscape and Urban Planning. (2016): 148, 149-158.

Dettweiler, U., Becker, C., Auestad, B.H., Simon, P., and P. Kirsch. “Stress in school. Some empirical hints on the circadian cortisol rhythm of children in outdoor and indoor classes.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. (2017): 14(5).

Meredith, G.R., Rakow, D.A., Eldermire, E.R.B., Madsen, C.G., Shelley, S.P., and N.A. Sachs. “Minimum time dose in nature to positively impact the mental health of college-aged students, and how to measure it: A scoping review.” Frontiers in Psychology. (2020): 14.

Twohig-Bennett, C. and A. Jones. (2018). The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and healthy outcomes. Environmental Research, 166, 628-637.