Erica Chambers, Program Officer, Health at the Sisters of Charity Foundation of Cleveland, is a member of the GIH HEAL Funder Learning Community, an intensive, longitudinal learning and networking experience exploring current and emerging opportunities and challenges facing foundations of all sizes, types, and approaches. This article is inspired by the deliberations of the learning community at the 2017 GIH Annual Conference on Health Philanthropy. If you would like to know more about the learning community’s work, please contact Colin Pekruhn.

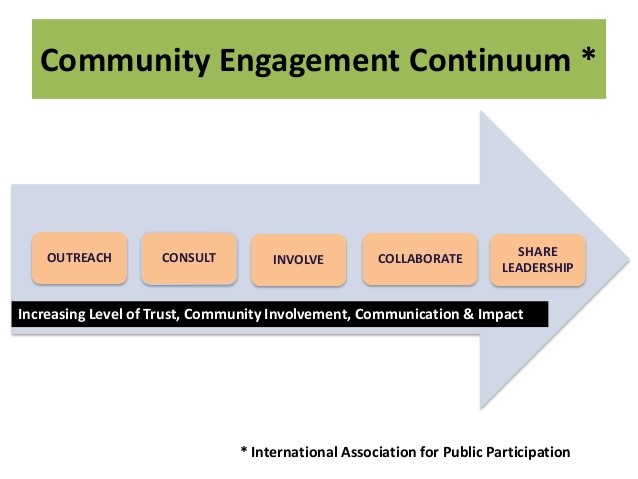

Community engagement has become a somewhat ubiquitous term within the social sector, which often oversimplifies a deep and complex process. At its best, community engagement describes a continuum of strategies that move a collective group of people from some level of involvement (e.g. outreach) to full participation in decision making (e.g. shared leadership), building momentum for community organizing (CDC and ATSDR, 2011; Murphy, 2013).

In philanthropic practice, community engagement often involves outreach to grantees who funders rely on to tell us about the people we seek to impact. While some nonprofits have deep connections with the people they serve, many nonprofits are ultimately representatives of representatives. Philanthropy’s true end users—disenfranchised people—often have limited engagement with foundations, and they are often poorly represented at decision making tables. To better engage disenfranchised people and have greater success in improving health outcomes, philanthropy must better understand and utilize community engagement, by working directly with community organizers and by supporting organizations that employ community organizing principles.

Lessons Learned as a Community Organizer

I have spent the last decade working in the nonprofit and public sectors. Prior to philanthropy, I led a multistakeholder community health coalition focused on healthy eating and active living (HEAL). The experience solidified my respect for the field of community engagement and organizing, and I learned several valuable lessons that I believe can benefit funders:

- Community engagement and organizing is an iterative process, balancing a series of actions to move the community forward and produce tangible results. Community organizers constantly hold the tension created by engaging in civic discourse. Finding the right balance of addressing community need, interest, and action takes time. It is about building one-on-one relationships, and trust is key. By taking the time to build relationships with grantees, funders can better anticipate real-time community dynamics and tailor support and expectations accordingly, especially if their work focuses on vulnerable populations.

- Evaluating community driven initiatives may require nontraditional frameworks. Few practitioners in the community engagement and organizing space are trained to design and evaluate multicollaborative initiatives, and many struggle to describe impact in a way that resonates with funders. Language and methodology barriers can arise for grassroots professionals who want funders to understand impact beyond numbers. Funders should be open to alternative ways to define success and should consider supporting grantee evaluation capacity.

- Community engagement and organizing are equity in motion. Grassroots practitioners often come from communities of color or other disenfranchised backgrounds. The HEAL coalition I led was intentional about reflecting the demographics of neighborhoods. We created a structure for decision making, giving residents autonomy to create their own HEAL initiatives. Funding approaches that use resident-driven strategies help ensure that equity is at the forefront.

- Race and power dynamics are real in philanthropy. Philanthropic leadership does not often reflect the race or socioeconomic status of the people they seek to serve. A 2015 Council on Foundations (COF) report found, of the 267 national respondents, 8 percent of CEOs and 24 percent of full-time staff positions, including program officers, were people of color (COF, 2015). There is an inherent power structure in philanthropy, coiled in the mesh of race, class, and implicit bias. In funding disenfranchised communities, it is important for funders to explicitly acknowledge the role of race and class and create opportunities to address it institutionally.

Using Community Engagement to Improve HEAL

The Sisters of Charity Foundation of Cleveland (the foundation) has a long history of walking alongside people in poverty. It started with the Sisters of Charity of St. Augustine, Cleveland’s first public health nurses who arrived from France in 1851, who established hospitals and human service organizations for disenfranchised people. Since 2009, the foundation has invested in place-based strategies to improve access to HEAL and economic opportunities in the Central Neighborhood of Cleveland, a community experiencing multigenerational poverty and poor health outcomes. Below are two examples of how our partners lead with equity, community engagement and organizing, and resident voice to drive neighborhood change.

One Garden Valley Initiative. Environmental Health Watch, a long-time partner of our foundation, formed One Garden Valley: a youth-led council, founded in partnership with Garden Valley Neighborhood House, to create food and music-related economic opportunities for residents. Guided by community engagement principals and resident voice, the initiative provides leadership, business, and entrepreneurial training for youth interested in culinary and music social enterprises in the neighborhood. History, health, and healing education is embedded across activities, including the youth-run EATS Café, which serves healthy, low-cost meals to community residents. In its first year, the cafe generated enough revenue to cover operational costs. The work of the initiative is done in collaboration with Rid-All Green Partnership (an urban agriculture production and education business); Fresh by Nature Records (an independent music company led by women of color); and Burten, Bell, Carr Community Development, Inc. In partnership with The Kresge Foundation’s FreshLo initiative, our foundation supports this work that placesracial equity and social justice at the forefront.

Building Healthy Communities. Starting in 2004, Building Healthy Communities (BHC) has partnered with residents to improve HEAL access among Central Neighborhood youth. BHC has created resident-led physical activity programs, cooking classes for youth and parents, and other neighborhood leadership activities (e.g., voter registration campaigns). One of BHC’s most successful programs is the Garden Boyz Initiative. Created by residents in 2008, the initiative mentors and empowers boys of color to be leaders in their community and help improve conditions of blighted property surrounding public housing. The youth now own two plots of land, are master gardeners, and have started a market garden that has grown from selling produce to a few local non-profits to partnerships with surrounding hospitals. Our foundation funds BHC’s programmatic work and supports organizational capacity building.

In addition to supporting organizations that employ community organizing principles to improve HEAL access, the foundation continues to explore new ways to approach equity and community engagement:

Community-Based Participatory Asset Mapping. Earlier this year, the foundation formed a steering committee of residents and grantees to design a community asset mapping engagement strategy. The goal was to gain on-the-ground resident input to explore strengths, challenges, and opportunities to improve neighborhood health. Along with focus groups and key-stakeholder interviews, the results of this work inform the foundation’s health strategies while deepening trust and relationship in the community.

Racial equity. In a recent assessment, our foundation’s board revealed it wants to better understand how to actualize practices that support racial equity. To that end, our board and staff are exploring the tenants of structural racism by participating in Racial Equity Institute (REI) trainings. REI uses historical facts and data to show how race has implications in every American institution, and the training provides resources to grow an organizational culture that embraces social justice.

Philanthropy Moving Forward

As a field, philanthropy has made great strides in improving health equity. Our ability to pivot and explore new approaches will continue to help us achieve our greatest impact. We should intentionally:

Explore the benefits of investing in equity and community engagement. There are many examples from institutions such as PolicyLink, GrantCraft, The Center for Effective Philanthropy, the National Collaborative for Health Equity that discuss the added value of investing in the community to drive change. A first step may be to provide small community grants to grassroots organizations or support innovative community engagement strategies such as the Smart Chicago Collaborative or Fresno Building Healthy Communities.

Invest in nonprofit capacity building. Support the development of community engagement efforts by investing in operational grants, leadership development opportunities, organizer training, and evaluation. Funding projects is important, but having a strong infrastructure and capacity to get the work done requires financial support as well. Be open to developing long-term relationships and sustained partnerships. Additionally, connect developing grassroots initiatives with community organizing veterans who can help develop their capacity. Funders can use their organizational and human capital to enlarge partner networks.

Lead with fairness and justice. Foundations should be open to reflecting on their values and principles as they relate to power, race, and class. We live in an inequitable society that adversely affects the poor and people of color. Community engagement and organizing are powerful tools grantmakers can use to create lasting impact among disenfranchised people. By engaging directly with community organizers, the field of philanthropy can find new paradigms for how to address health equity. In this time of social and political upheaval, we must go outside our comfort zone and build new partnerships in civic engagement that will propel philanthropy to its next phase. Lean forward into the discomfort of civic discourse; this is where healing and learned empathy begin.

References

Agency for Toxic Disease Registry. The Principles of Community Engagement. 2nd ed. NIH Publication, 2011. Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf

International Association of Public Participation (2014). Public Participation Guide: Selecting the Right Level of Public Participation. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/public-participation-guide-selecting-right-level-public-participation

Murphy, F. G. (2013). Community Engagement, Organizing, and Development for Public Health Practice. New York, NY: Springer.